Adoration of the reflected

- Suvarup Saha

- Jul 1, 2025

- 3 min read

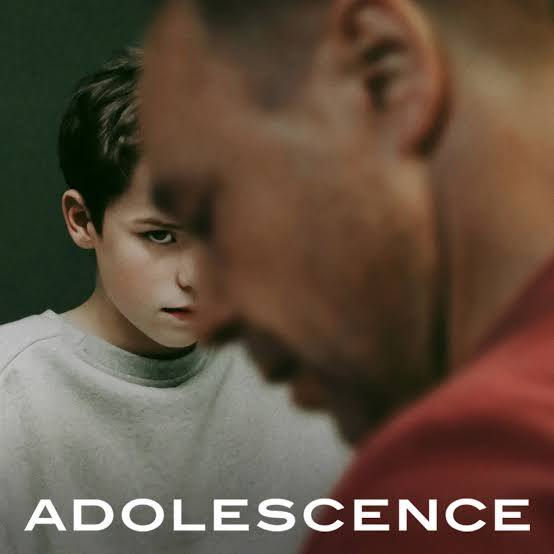

For a millennial parent of an eleven year old, watching Adolescence on Netflix seemed to be an urgent qualifying exercise, chided by the posse of friend/family recommendations this four-episode limited series commanded. While a lot of this chatter revolved around the glimpses of the gen-Alpha language and its emoji grammar, the strength of the show perhaps rests elsewhere. It is incredible that the tightly wound script could afford to spend a quarter of its airtime in a psychological evaluation and a tad less on a birthday breakfast that never materialised, and yet, never lose the uneasy tension it injects. But what transcends the did-he-do-it and the why-did-he-do-it is the powerful yet delicate handling of several fundamental questions that will always cloud a parent-child relationship. And along the way, the makers of the show slice our human experience as a depraved security officer, a vulnerable psychologist, an yielding but punchy detective sergeant or a hopeless high school teacher, to bother and rattle the stupor hanging around the equilibrium of our quotidian.

For me personally, watching the show brought to the fore many images and lines from some books and essays that have been shaping my understanding of parenthood.

In A little Life, Yanagihara writes, We all say we want our kids to be happy, only happy, and healthy, but we don't want that. We want them to be like we are, or better than we are. We as humans are very unimaginative in that sense. We aren't equipped with for the possibility that they might be worse. In the show, the father, Eddie Miller had anger issues, and he could perhaps link to an inheritance, the beatings that he received as a child from his father. He has methodically shielded his son from it, and yet, there he is, being the appropriate adult for his son's trial as a murderer. And there is a part of him that must be gnawing at his being, staring at the rage that he believes has has passed on to his son.

In the same book, Harold, the adopted father of the protagonist, says - when your child dies, you feel everything you'd expect to feel, feelings so well-documented by so many others that I won't even bother to list them here, except to say that everything that's written about mourning is all the same, and it's all the same for a reason - because there is no read deviation from the text. Sometimes you feel more of one thing and less of another, and sometimes you feel them out of order, and sometimes you feel them for a longer time or a shorter time. But the sensations are always the same....But here's what no one says - when it's your child, a part of you, a very tiny but nonetheless un-ignorable part of you, also feels relief. Because finally, the moment you have been expecting, been dreading, been preparing yourself for since the day you became a parent, has come. Jamie, the show's thirteen year old murder accused, did not die. He, in all likelihood killed a classmate. But perhaps Eddie's worst fears have finally come true, and there is nothing more to fear after that.

Years back, when our son was just two years old, A gifted me Ta-Nehisi Coates' Between the world and me. I was not living the black experience in America that makes Coates write Think of soccer balls, science kits, chemistry sets, racetracks and model trains. Think of all the embraces, all the private jokes, customs, greetings, names, dreams, all the shared knowledge and capacity of a black family injected into that vessel of flesh and bone. And think of how that vessel was taken, shattered on the concrete, and all its holy contents. But we were still immigrants, being shaped by a brown experience of our own, with Trump's election and guns ringing in elementary schools. And for Manda and Eddie, it is perhaps the algorithms that they must stare at, as the faded neons of the detention facility now holds their son.

As a parent, we want to be the wizard or the witch who can cast a Protego Totalum spell and keep them shielded, forever. In The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson's imagining of a half-scissor sticking out of her newborn's head is also perhaps talismanic, an enactment of the worst that could happen, so that it doesn't. And in that protection lies her baby Iggy, sick, and his mother's memory of a loop of time.. that is removing the side of a raised hospital crib in the morning light and climbing into it beside him, unwilling to move or let go or keep living until he lifted his head, until he gave any sign that he would make it out. For Manda and Eddie, their protective charm had perhaps failed, momentarily. And I watch out for signs of such breaches of my own.

Comments